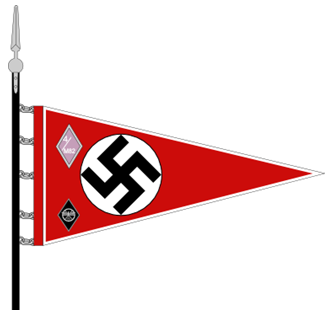

NSKK Storm Pennant

This pennnant is that of NSKK Storm 4, Standard 82, and because of the pink panel this storm belonged to the group "Mark Brandenburg."

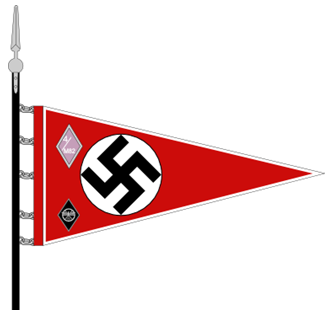

NSKK Corps Leader

Vehicle Command Flag

|

The National Socialist Motor Corps Flags 1931-1945

(Nationalsozialistisches Kraftfahrkorps)

The National Socialist Motor Corps (NSKK), also known as the National Socialist Drivers Corps, was a paramilitary organization of the Nazi Party. It was headed by Adolf Hühnlein from 1934. After Hühnlein's death in 1942, Erwin Krauss took over his position as Korpsführer (Corpsleader). The primary aim of the NSKK was to educate its members in motoring skills. With the outbreak of World War II in 1939, the National Socialist Motor Corps became a target of the Wehrmacht for recruitment, since NSKK members possessed knowledge of motorized transport. In 1945, the NSKK was disbanded and the group was declared a "condemned organization" at the Nuremberg Trials.

NSKK General House Flag

The "House Flag," or General flag of the NSKK consisted of a red background on which was centered the eagle of the NSKK on a white disk. The wings of the eagle reached a little bit into the red field of the flag. The NSKK was organized similar to the SA, i.e. there were "groups" (Gruppen), "standards" (Standarten) and "storms" (Stürme), respectively.

A NSKK-storm received a pennant with a red, white bordered background and a black swastika on a white disk. In the top left corner of the pennant appeared the storm-number and below the standard number on a lozenge-shaped panel. The panel displayed the color of the Motor-Group. In the lowest left corner was the special NSKK badge. This lozenge-shaped, black badge consisted of the Party eagle that was laid on a stylized wheel. The leaders of the NSKK were allowed to use a Command flag as vehicle flag. For the Corps leader, it was a white, black bordered square, diagonally crossed by a red stripe. The eagle of the NSKK and below the word "Korpsführer" (Corp Leader), both in silver were displayed on the red and white areas.

|

On 9 March 1938, in an effort to preserve Austria's independence, Schuschnigg scheduled a plebiscite on the issue of unification for 13 March. To secure a large majority in the referendum, Schuschnigg set the minimum voting age at 24, as he believed younger voters were now supporters of the German Nazi ideology. This was a risk, and the next day it became apparent that Hitler would not simply stand by while Austria declared its independence by public vote. Hitler declared that the referendum would be subject to major fraud and that Germany would not accept it. In addition, the German ministry of propaganda issued press reports that riots had broken out in Austria and that large parts of the Austrian population were calling for German troops to restore order. Schuschnigg immediately responded publicly that reports of riots were false.

Hitler sent an ultimatum to Schuschnigg on 11 March, demanding that he hand over all power to the Austrian National Socialists or face an invasion. The ultimatum was set to expire at noon, but was extended by two hours. Without waiting for an answer, Hitler had already signed the order to send troops into Austria at one o'clock. Schuschnigg desperately sought support for Austrian independence in the hours following the ultimatum. Realizing that neither France nor Britain was willing to take steps, he resigned as chancellor that evening. In the radio broadcast in which he announced his resignation, he argued that he accepted the changes and allowed the Nazis to take over the government 'to avoid the shedding of fraternal blood.

Also to be noted, it is said that after listening to Bruckner’s Seventh Symphony, Hitler cried: "How can anyone say that Austria is not German! Is there anything more German than our old pure Austrianness?"

On the morning of 12 March, the 8th Army of the German Wehrmacht crossed the border to Austria. The troops were greeted by cheering Austrian Germans with Nazi salutes, Nazi flags and flowers. Because of this, the Nazi annexing is also called the Blumenkrieg (war of flowers), but its official name was Unternehmen Otto.[10] For the Wehrmacht, the invasion was the first big test of its machinery. Although the invading forces were badly organized and coordination among the units was poor, it mattered little because no fighting took place.[citation needed]

Hitler's car crossed the border in the afternoon at Braunau, his birthplace. In the evening, he arrived at Linz and was given an enthusiastic welcome in the city hall.

Hitler's travel through Austria became a triumphal tour that climaxed in Vienna, on 2 April 1938, when around 200,000 German-Austrians gathered on the Heldenplatz (Square of Heroes) to hear Hitler proclaim the Austrian Anschluss.[11] Hitler later commented: "Certain foreign newspapers have said that we fell on Austria with brutal methods. I can only say: even in death they cannot stop lying. I have in the course of my political struggle won much love from my people, but when I crossed the former frontier (into Austria) there met me such a stream of love as I have never experienced. Not as tyrants have we come, but as liberators."

The Anschluss was given immediate effect by legislative act on 13 March, subject to ratification by a plebiscite. Austria became the province of Ostmark, and Seyss-Inquart was appointed governor. The plebiscite was held on 10 April and officially recorded a support of 99.7% of the voters.

Voting ballot from 10 April 1938. The ballot text reads "Do you agree with the reunification of Austria with the German Reich that was enacted on 13 March 1938, and do you vote for the party of our leader Adolf Hitler?" The large circle is labelled "Yes", the smaller "No".

Hitler's forces worked to suppress any opposition. Before the first German soldier crossed the border, Heinrich Himmler and a few SS officers landed in Vienna to arrest prominent representatives of the First Republic, such as Richard Schmitz, Leopold Figl, Friedrich Hillegeist and Franz Olah. During the few weeks between the Anschluss and the plebiscite, authorities rounded up Social Democrats, Communists and other potential political dissenters, as well as Jews, and imprisoned them or sent them to concentration camps. Within only a few days of 12 March, 70,000 people had been arrested. The plebiscite was subject to large-scale propaganda and to the abrogation of the voting rights of around 400,000 people (nearly 10% of the eligible voting population), mainly former members of left-wing parties and Jews.

While historians concur that the result was not manipulated, the voting process was neither free nor secret. Officials were present directly beside the voting booths and received the voting ballot by hand (in contrast to a secret vote where the voting ballot is inserted into a closed box). In some remote areas of Austria, people voted to preserve the independence of Austria on 13 March (in Schuschnigg's planned but officially cancelled plebiscite) despite the Wehrmacht's presence. For instance, in the village of Innervillgraten, a majority of 95% voted for Austria's independence. However, in the plebiscite on 10 April, 73.3% of votes in Innervillgraten were in favor of the Anschluss, which was still the lowest number of all Austrian municipalities.

A largely unhindered voting process occurred in the Italian harbour city of Gaeta, where an extraterritorial vote of German and Austrian clerics, studying at the German college of Santa Maria dell'Anima, took place. The vote was concluded on board the German cruiser Admiral Scheer, which was anchored in the harbour. Contrary to the overall result, these clerical votes rejected the Anschluss by over 90%, an incident which became known at the time as the "Shame of Gaeta".

Austria remained part of the Third Reich until the end of World War II, when a preliminary Austrian government declared the Anschluss null und nichtig (null and void) on 27 April 1945. After the war, then Allied-occupied Austria was recognized and treated as a separate country. It was not restored to sovereignty until the Austrian State Treaty and Austrian Declaration of Neutrality, both of 1955, largely due to the rapid development of the Cold War and disputes between the Soviet Union and its former allies over foreign policy.

|

Back to Grahams Nazi Germany Third Reich Covers

Back to Grahams Nazi Germany Third Reich Covers